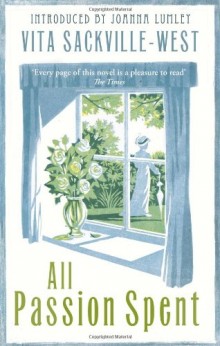

All Passion Spent

All Passion Spent

General Fiction

Virago Modern Classics

1982

193

The story of the life of Vita Sackville-West is as fascinating as any novel. Most famously she was the close friend and lover of Virginia Woolf. This is not merely a salacious titbit but part of the information imparted in Victoria Glendinning’s introduction to All Passion Spent. Information that lends much to the understand of Sackville-West and her creation, Lady Slane.

Lady Slane is a newly widowed octogenarian. Her husband was a great politician, an “old landmark” and father of their six children – now “large and black and elderly, with grandchildren of their own”.

In the wake of his death these children congregate like large black crows in their parent’s home to discuss their mothers fate. They decide for her that she cannot possibly live alone and fend of herself and most be sorted out by them. She is seen as both a burden and extra income.

Lady Slane who has been seen as “all her life long, gracious and gentle, she had been wholly submissive – and appendage” without opinion of her own or great intellect, has a surprise for her offspring. For the first time in the seventy years of marriage and motherhood she has taken charge and is doing exactly as she wants, “I am going to be completelyself-indulgent. I am going to wallow in old age…I want no one about me except those who are nearer to their death than to their birth.” What she wants is to live alone with her elderly French maid in a house unfitting of her stature in Hampstead.

The house is one she has seen thirty years ago and finds still waiting for her as she expects. The house itself is as strong a presence as an old friend. Here Lady Slane settles into a happy reflection. She makes friends with the landlord of her new home and his builder, who do up the long empty house while enjoying the regal lady’s company and she renews a friendship of long ago. Although these are new developments she spends much of her life contemplating her memories, oft going back to her time before marriage when she has her whole life ahead of her. In these ruminations she remembers when at seventeen he wanted to become an artist – this is more a wish for independence that any real desire to create art; as she admits she has never even picked up a brush to paint.

After decades of fulfilling others wishes and expectations Lady Slane has created a space of her own. Although placing herself as a reluctant bride and mother she does not completely damn this state; while free of them she finds pride and interest in the family, keeping newspaper cuttings of their accomplishments. Her family also bring her another unexpected vicarious fulfilment in the form of her granddaughter Deborah “This child, this Deborah, this self, this other self, this projection of herself” who calls off her engagement to follow her own passion – to become a musician, an echo of a past path now lost to Lady Slane.

This is not merely a fictive work but a meditation on Victorian women’s freedom, expected roles and status and in particular one woman’s ruminations on life and bring true to oneself, this woman being not just Lady Slane but Sackville-West herself. ![]()