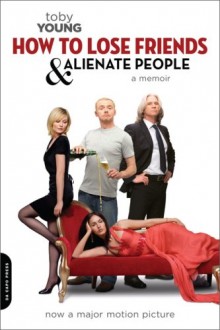

How to Lose Friends and Alienate People

How to Lose Friends and Alienate People

Biography

Little, Brown Young Readers

2008

349

At some point in their career, most journalists dream of conquering the land of Manhattan’s glossy mags. Undeterred by a world where infamous ball-breaker Tina Brown is Queen, Toby Young went Stateside for five years in search of success, supermodels and better cocaine. Thus begins a voyage of self-discovery bristling with a naivety that rarely leaves his narrative.

On arriving in the US, Young observes, “Landing at JFK is the modern equivalent of arriving at Ellis Island at the beginning of the Twentieth Century”. Surely not, when your flight is paid for and a Vanity Fair expense account awaits you? This triteness litters the book – he refers to his dead mother as ‘Obi-Wan Kenobi’ and ruminates on a night spent researching a story dressed as a woman: “Forget about Kosovo. This was the most dangerous journalistic assignment of the 90s”. Indeed, Toby.

In career terms, Young’s five-year stint at Vanity Fair proves to be a fairly damp squib. But it provides the perfect platform for Young’s British humour, which manifests itself as social faux pas and political incorrectness to his stuffy NYC colleagues. In one incident at the Condé Nast offices, he hires a stripper for a friend’s birthday – only to discover it is ‘Bring Our Daughters To Work Day’. Needless to say a memo on sexual harassment is swiftly despatched to his desk.

As a thirty-something hack in a shark-pool of fashion vacuity, he details his efforts at jumping on the coat-tails of the glitterati. His attempts to crash Oscar parties or schmooze celebrities end in cringe-inducing failure but provide some of the funniest moments in the book. While many of these episodes are given a comedic spin, Young’s frankness about his experiences is refreshingly honest. Much of his writing is sloppy, which may be due to hazy recollections given Young’s alcoholism for much of this period. His stories are filled with repetitive, lazy descriptions used over again – door girls at glitzy parties are ‘clipboard nazis’ while the wealthy young women who repeatedly snub him are ‘Park Avenue princesses’. His infantile rivalry with fellow journalist Alex De Silva reflects badly on him, painting him as a bitter hack. Young ponders his lack of luck with women throughout, but the amount of gauche sexism in the book should give him his answer.

Toby Young’s account of his lacklustre efforts in Glossy land is narcissistically clichéd but saved from trashiness by his self-deprecating humour. It may take him five years, but he eventually realises that the ersatz world of Big Apple publishing is more about who you know and how much money you make than who you are.

In Young’s David and Goliath tale, Goliath triumphs but not before the underdog has achieved a couple of things – by undermining the vainglorious reputation of the Manhattan glossies and in revealing their inability to laugh at themselves, Young has the last laugh. ![]()