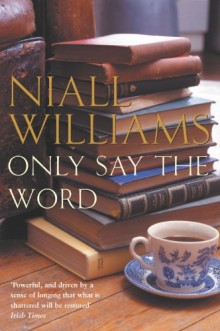

Only Say the Word

Only Say the Word

General Fiction

Picador

400

This book blew me away with its relentless sense of longing, a yearning shot through with glimmers of hope that are constantly knocked back down. It’s a book about death and love (of people and place), the search for a sense of meaning in life and, perhaps most interestingly, the agonising process of writing itself.

The story is driven by an unasked question: how to merge the past with the present in a way that makes sense. Structured around two parallel narratives, it begins with the words of Jim Foley, a writer, who is penning a kind of love letter in the form of a computer diary to his wife, Kate. In it he documents his present life, his struggles with writing and bringing up their two children, in the aftermath of her death. This ongoing narrative is interspersed with the text of the book Jim is writing, in which he recounts the story of his own childhood, upbringing, young adulthood and meeting with Kate.

The balance between truth and fiction is interesting as so much of this book is chronologically true to author Niall Williams’ own life: like Jim, he too studied English and French literature at college in Dublin; he moved to New York in 1980 where his first job was in a bookstore and where he married his American wife, whom he had met at college. Like Jim and Kate, Niall and his wife returned to Ireland in 1985, moving to a cottage in West Clare: him to write and her to paint. But the main focus of the book, the death of Jim’s wife, is a fiction.

Present-day in the book is 2001/02, and it emerges that much of Jim’s motivation to write, and by remove Niall Williams’, comes from a reaction to the events of September 11th. Some of the most interesting passages concern the effect of the terrorist attacks on Jim’s teenaged daughter, Hannah. For Irish readers, there are in-joke references to the iodine tablets debacle and that infamous radio interview with a certain government minister.

The main character, Jim, is a man immersed in reading and books. Williams’ merges Jim’s childhood reading into the text, revealing how Dickens’ Great Expectations shaped his view of the world. Everyone in the book seeks their own escape from reality: Jim’s brother through study and eventual flight, his children through television, himself through reading.

There are many layers to this book, but what sustains it throughout is Williams’ lyrical prose. His timing is immaculate; there was no place where I longed to go back to one narrative whilst in the middle of the other. He is also a master of creating and sustaining an atmosphere, making almost tangible the silences between people, the things that go unsaid, the pain and anger bubbling beneath the surface: “I stand in the doorway and do nothing once more, as the moment is taken and folded carefully and placed inside of me.” “His lips are drawn tightly together as if he holds there a mouthful of thorns.”

It’s also a book about faith and whether it’s possible to cope with loss without some kind of belief in God or a higher power. And perhaps most poignant of all, it’s about the terrifying burden of trying to be to be a good son, and then a good father, alone.

My only fault is with the Afterword, which broke the suspension of disbelief in which I was happily floating, but nonetheless this goes on my highly recommended list: it’s a heart-rending read, elevated by Williams’ beautiful prose. ![]()